In order to produce high-quality digital copies of about 250 Flemish masterpieces, our project involved photographing, digitising and 3D-scanning paintings, sculptures, maps, handwritten documents, old prints... to name but a few! Each type of work is unique and therefore requires a completely different approach.

The majority of digitisation projects carried out by meemoo, the Flemish Institute for Archives, in recent years have been mass digitisation projects. This means bringing together a vast number of the same type of carriers from various organisations. They are then packaged, registered, sent to a digitisation company, digitised and archived – all at once – as is the case for newspapers or glass plates, for example.

Digitising masterpieces, however, requires a different approach. Each object is so different that it does not make sense to treat them in bulk. The method used also depends on the desired result, which is why this project used four different approaches.

In July 2021, half of the masterpieces on the Flemish List of Masterpieces did not yet have a high-quality digital copy. The GIVE project can therefore be called a catch-up initiative for digitising Flemish masterpieces. But how did we decide which masterpieces to select for digitisation? Well, we removed from the list any works that had already been digitised to a high standard, and prioritised works that were difficult to access. This includes some works that are hanging several metres high in the air, or located in a remote corner of Flanders, or not accessible to the public at all. The masterpiece also had to be available during the digitisation period. The entire selection process was carried out in close consultation with the Flemish Masterpieces Board, which assigned a priority score to each work, and the institution that manages the collection itself.

The GIVE project was also a real learning experience, involving techniques and types of objects that were new to meemoo. That is why such a diverse set was chosen, in terms of:

geographical distribution

materials

custodians

Specific guidelines were also established for certain digitisation techniques, which you can discover below.

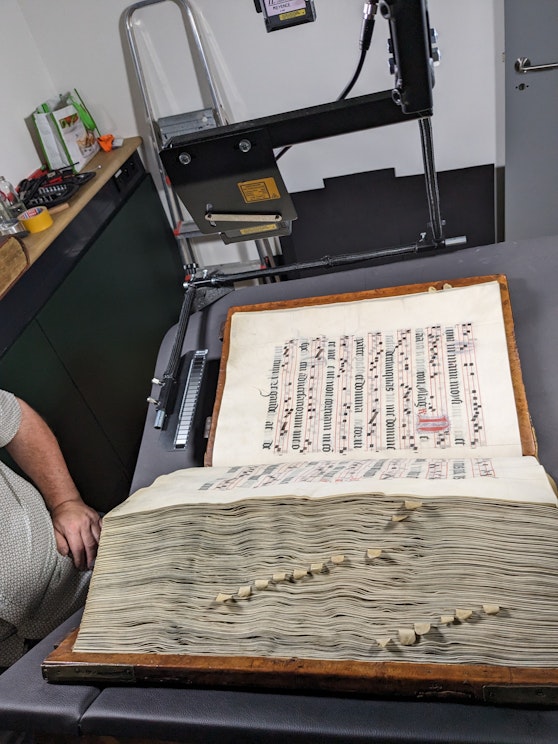

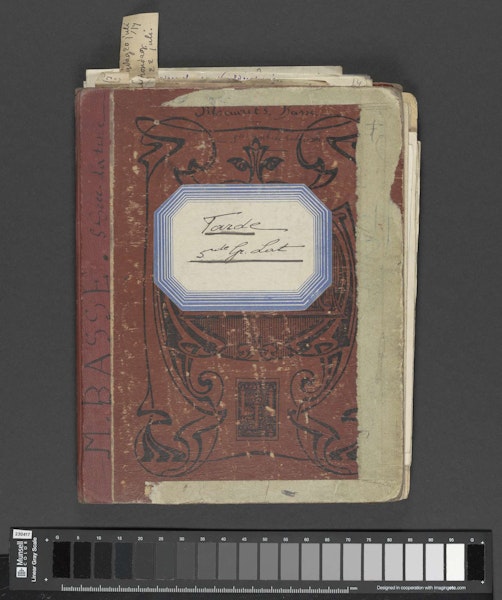

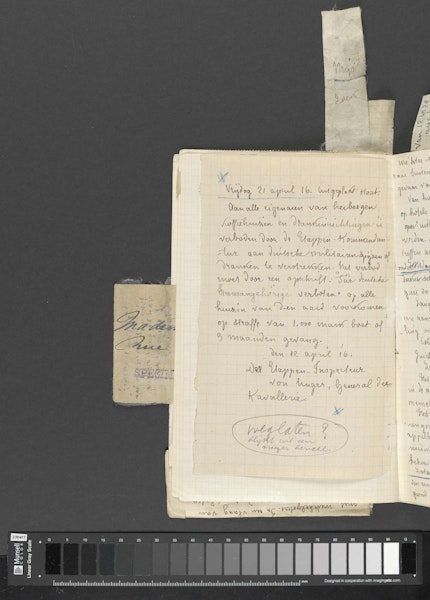

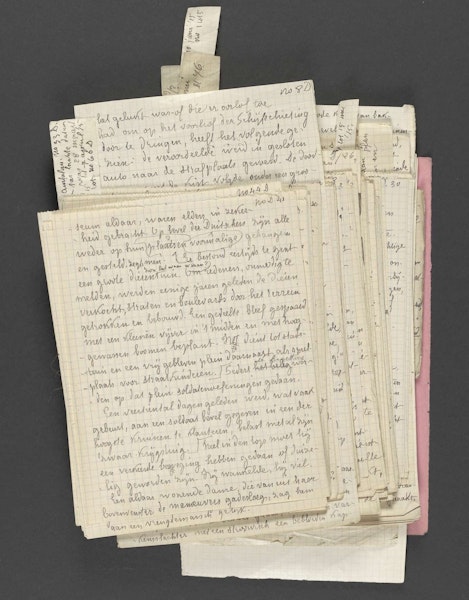

In the first part of the project, we used a mobile book cradle to digitally capture 25 masterpieces (40 works in total, because some masterpieces consist multiple works) made from paper or parchment, including choir books, scraps of paper from a literary diary, stained glass patterns, sheet music, theatre scripts, compiled handwritten documents and more. This cradle had to meet high-quality standards and be able to handle a variety of objects and locations. The digitisation took place on-site – in situ – with the custodians, and was quite a challenge!

Why do we refer to ‘handwritten documents and old prints’ instead of the more common term ‘manuscripts’? Well, a manuscript is literally a handwritten document, but not all works on the list fall under this category because some of them are printed. So that’s why we refer instead to ‘handwritten documents and old prints’.

What stands out about this project is that the preparation took much longer than the actual digitisation itself. We captured 37 handwritten documents and 3 old prints in photos over 39 days, but the preparatory steps took nearly two years: from selection to condition reporting and site visits, and bringing in experts.

A crucial step in this process is the creation of a tender document. This document provides information about the desired process, minimum requirements for the digitisation outcome, and practical details. It will ultimately help you confidently select the most suitable digitisation partner.

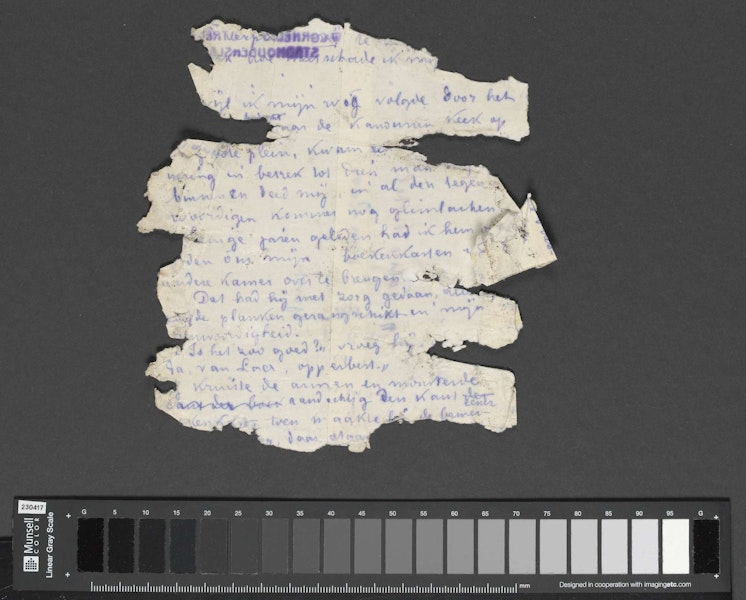

This involves assessing the condition of a heritage object and determining whether it can withstand the digitisation process in its current state. It also involves determining whether a work needs pre-treatment or restoration, such as dry cleaning, stopping any tears from worsening or restoring a historical binding. The most important characteristics are noted globally and per folio (size, tears, ink corrosion, presence of loose fragments, etc.) Some additional guidelines for digitisation are also essential, such as the maximum opening angle, recommended support tools or the sensitivity of the ink to (sun)light exposure.

Due to the unique nature of all custodians, locations and objects, we conducted a total of 44 site visits in order to…

examine the works and their condition;

carry out condition reporting;

solve any logistical issues;

share knowledge and make agreements;

select the appropriate digitisation space;

identify any environmental factors that could affect digitisation.

Martine Eeckhout was responsible for the condition reporting, and we also enlisted the expertise of Flanders Heritage Library, the Public Library of Bruges and the Flemish Masterpieces Board. Hans van Dormolen was also involved to help with compliance with the strict Metamorfoze guidelines, providing advice on applying this standard to the digitisation process.

A unique feature in this project is that we compiled a main and reserve list upon request from the Flemish Masterpieces Board. This reserve list could be called upon when an object from the main list could not or should not be digitised, for example because it was in too poor a condition. All works on the reserve list went through the same preparations as the main works, so everything could be done safely without any surprises.

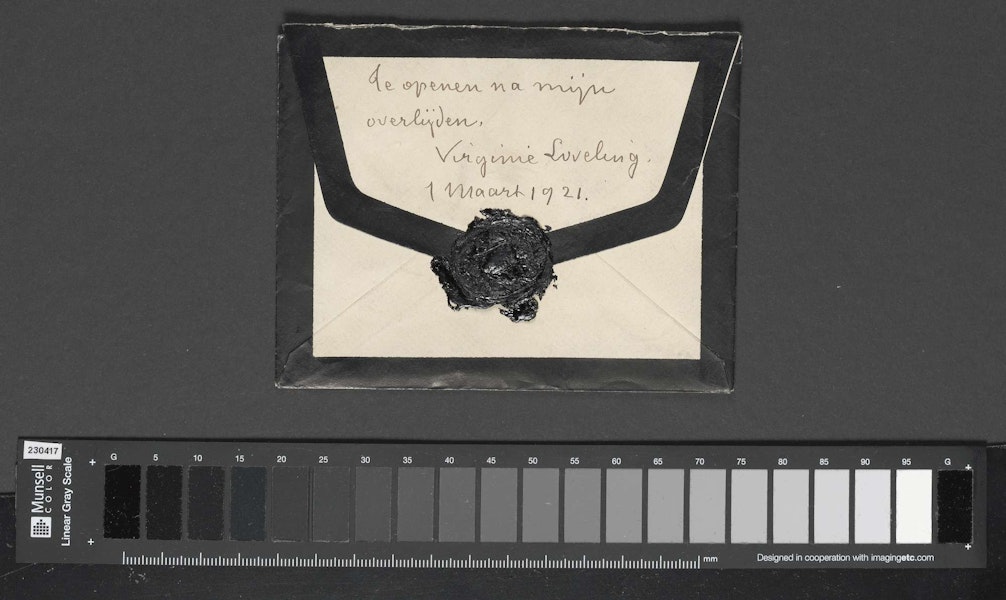

Some carriers, such as newspapers, can be seen as a pure source of information. Other heritage items are less easily separated from the context of their object. If the masterpiece is made from paper or parchment, for example, we opted to classify them in the latter category in the GIVE project. This has consequences for the way they are digitised, and we chose photography instead of scanning, with numerous additional shots taken: the cover, a clasp, small fragments, every blank page, a bookmark… nothing escapes our attention.

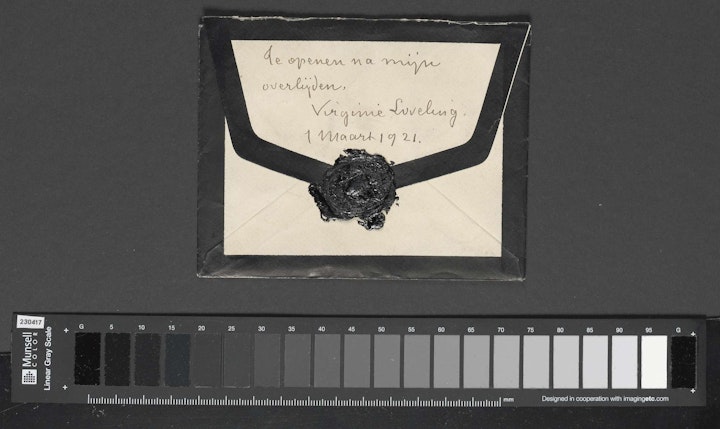

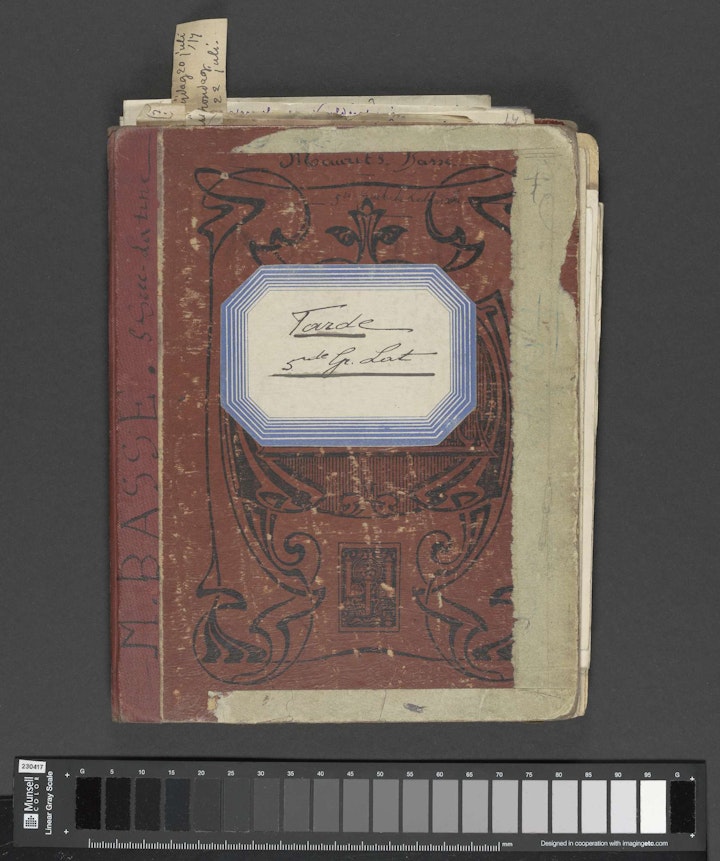

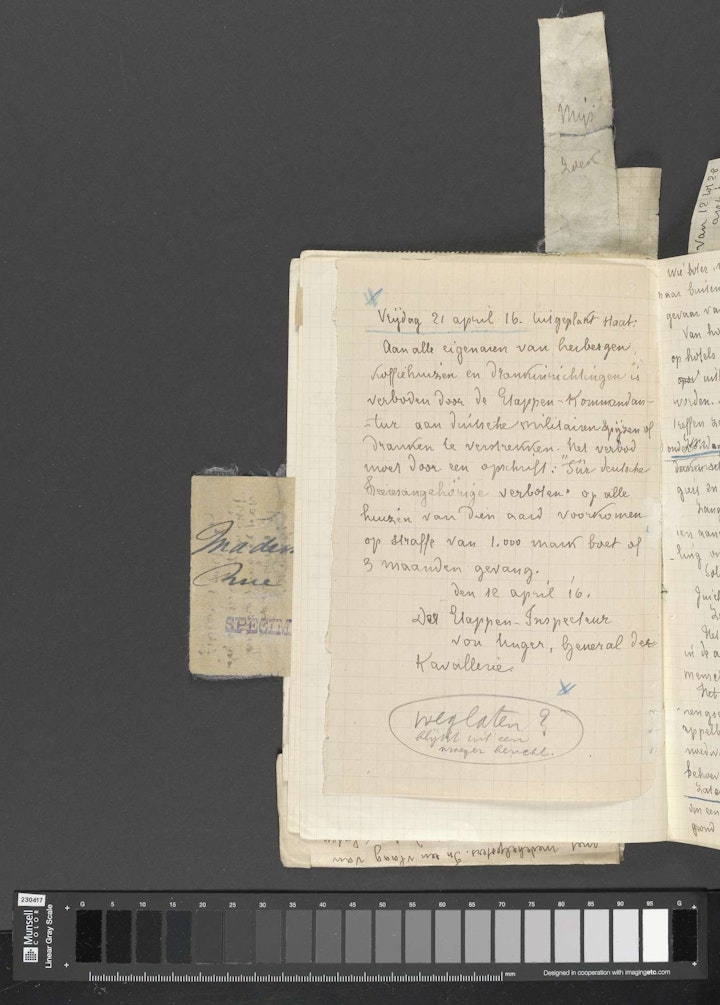

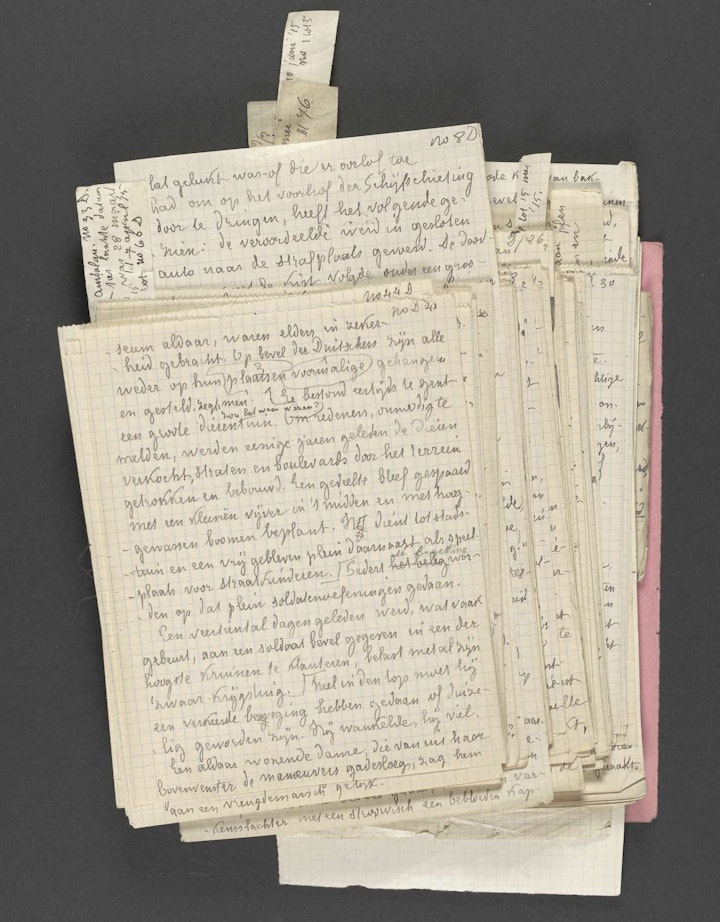

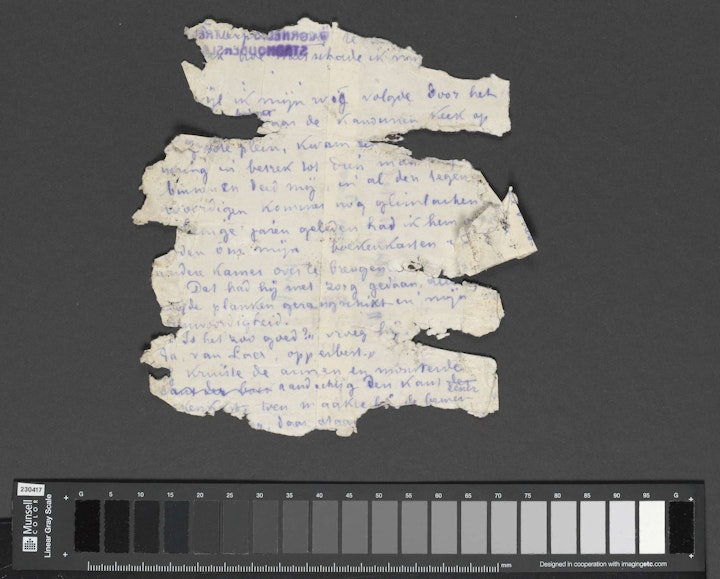

The war diaries of Flemish writer Virginie Loveling are a perfect example of this – with fragments of paper, sewn or glued pieces in the diary, envelopes, newspaper articles, notes… a true work of art, not just a text. Form and content go hand in hand here, and we captured that as best as possible in the images.

Each item in this project is unique – in size, dating, weight, location, physical condition or the nature of the binding (bound or loose sheets). To capture this diversity, Dutch digitisation company GMS built a mobile book cradle specifically for this project, equipped with accessories and extensions, a high-quality camera, two lamps, lasers and additional middle sections. This allowed them to photograph masterpieces of different sizes and with different opening angles in the most challenging locations. The heaviest book on the cradle weighed 35 kilogrammes!

The cradle also came with accessories so that we could capture any details in the margin: masses of foam, intermediate pieces in various sizes and fishing line to position the works as optimally as possible.

The handwritten and old prints in this project were captured as unifolio. This means that only one of the two open pages is photographed at a time, instead of both pages simultaneously. Each masterpiece was therefore browsed through twice: once for the rectos, and once for the versos.

This method produces a higher-quality capture than a bifolio capture, where you work with only one camera that photographs two pages simultaneously. Bifolio capture was not even possible in most cases due to the limited maximum opening angle and not being able to use a glass plate.

Masterpieces are valuable works, so it’s important to incorporate sufficient protection! For example, we did not perform any of the testing on original masterpieces. Wet coats, lacquered nails and gloves (which risk losing grip) were all strictly forbidden in the digitisation room, and the task of moving or manipulating the works rested exclusively with the heritage managers and meemoo.

We carried out the digitisation process in accordance with the strictest Metamorfoze guidelines. This set of standards for digital photography presented some challenges. What did it mean for this project?

We hired a digitisation firm with an in-house specialist photographer.

The digitisation took place in a room as dark as possible to maintain consistent lighting throughout the day, and we used the Munsell Linear Greyscale to confirm the light consistency.

Using a glass plate for digitisation was not an option. Instead, we used a camera to capture a unifolio image of each page. With IIIF, the pages can later be clicked back together or side by side. Take a look!

Very science fiction: two laser beams ensured a uniform distance between the camera and the object, and an optimal opening angle.

Depending on the size of the work, we used a resolution of 300, 400 or 600 PPI to capture as much detail as possible.

Before the digital objects flow into the meemoo archive system, everything is subject to a thorough quality control process.

The next category in the GIVE project is sculptures. With the expertise of De Logi & Hoorne - Erfgo3D, we scanned 134 works from head to toe before converting these scans into a 3D model. Did you know that 3D digitisation has been one of the initiatives set by Europe itself since 2020? The European cultural heritage sector has only recently started paying attention to this relatively new technique, and experimentation is still ongoing.

There is a huge number of items on the list of masterpieces that would benefit from this type of scan. But digitising everything was impossible, so we had to make choices in this digitisation line as well. The main criterion is that the object must be a sculpture of a manageable size (less than 2 metres tall) that is less accessible to the general public. GIVE was also a real learning experience, and we therefore sampled as much diversity as possible in terms of:

geographical distribution;

types of material and texture, such as marble and wood;

the type of preservation institution;

the number of works per custodian: is it a whole collection of sculptures or just one piece?

Before you start digitising, it’s important to think about what you want to achieve. This will determine your quality requirements and technology. There are different ways to create a digital 3D model, for example, such as structured light scanning, laser scanning or photogrammetry. With the first two methods, an object and its geometry and texture are scanned using specialist devices, and the data is immediately processed into a 3D model. With photogrammetry, the object is photographed from all angles before software processes the photos into a 3D model.

In this project, meemoo chose structured light scanning based on:

Working in situ, it was crucial to ensure the completeness of the capture. This can be achieved with structured light scanning, as the different images are brought together on-site, rather than afterwards as with photogrammetry.

Post-processing of scans is minimal because all the images are already combined on-site, resulting in significant time savings.

Structured light scanning accurately captures the geometry of the sculpture, which is less the case with photogrammetry. This geometry is crucial if you want to create a 3D print. Structured light scanning also uses built-in cameras to capture colour and texture.

There were already projects in the heritage sector using photogrammetry, but scanning was still relatively unexplored. To make progress and learn from it, meemoo opted for scanning.

Curious about the approach for a 3D capture? There are two methods, depending on the size and weight of the object. Large sculptures are captured from different viewpoints using a handheld scanner. Smaller pieces are placed on a turntable and processed with a fixed scanning device.

During scanning, striped patterns from structured light are projected onto the object. The scanner records how the patterns deform when they hit the object, and can therefore calculate the dimensions of each object. Even the smallest details don’t escape attention. Once everything has been scanned, all the data is merged on-site into a single file. Built-in cameras add colour and texture, ultimately resulting in a true-to-life digital 3D copy.

3D-scanning in the Sint-Leonarduskerk Zoutleeuw.

Sounds simple, doesn’t it? Well, that’s not entirely true! The weight and location of many of the sculptures made the GIVE project more challenging. To scan objects in 3D, you need to be able to fully move around the object, and many of the sculptures therefore had to be moved. But you can’t lift sculptures that weigh hundreds of kilos on your own, so we hired a professional art handling firm to relocate the sculptures responsibly from one place to another.

It's also true that not all objects are equally scannable using structured light. For example, light doesn’t pass through or reflect from objects made of wood as it does for translucent or reflective objects made of silver or glass. The light doesn’t reflect directly but bounces off in all directions, making it much more difficult to determine the geometric structure.

Then the images are ready for quality control. We used Blender open source software for the 3D models, and paid particular attention to scrutinising the completeness of the scan. Since there are no standards yet for quality control of colour and texture in 3D models, meemoo, together with Mindscape 3D, wrote a manual, which you can consult here.

You can use the scans made by meemoo as the basis for 3D printing a perfect analogue copy. This allows the object to be consulted and even replicated in case of loss or damage as a result of disaster. Furthermore, the 3D models, whether printed or not, are ideal for conducting scientific research as the works themselves no longer need to be manipulated.

Photographing art and heritage collections in high resolution has been one of meemoo’s specialities for several years. Just take a look at artinflanders.be. Gathering expertise was therefore less applicable in this context. See below to discover the challenges we encountered.

Cedric Verhelst was behind the camera for the GIVE masterpieces project, taking high-quality photos of 175 paintings and prints. In addition to pieces from museums, we also looked at smaller collections with lesser-known or less accessible masterpieces.

Digitising museum collections or masterpieces in 2D requires quite a specific approach. Photographing a single museum piece is much more intensive than digitising a single carrier (such as a glass plate or newspaper). Whereas carriers are transported together to the digitisation location, digitising a painting or print is truly tailor-made work. The object cannot move, which means the work needs to be done in situ. And with works of art spread throughout Flanders, this can mean covering quite a lot of miles!

We visited dozens of locations in the GIVE masterpieces project. And, as diverse as these locations were, so were the situations in which we had to digitise objects: from items that were suspended several metres high in the air, to paintings in a secure climate box or with unpredictable lighting, changing shadows or curious museum visitors. We always assessed the current location of the artwork first to see if we could use it. If we still had to move it, the preservation institution itself or a hired art handling firm always carried out any possible manipulation.

Once the artwork was hanging or standing in the desired place, the next step was to capture the work alongside a target or colour chart. These targets allow you to check that the lighting at the chosen location is correct and the colour in the digital image is true to life. If necessary, we adjusted the lighting and setting before the artwork could be photographed in high quality. We enlisted a professional photographer for this task to ensure we captured high-quality digital reproductions.

The captures of the colour charts or targets are also useful for the next step: quality control. For the 2D works in the GIVE masterpieces project, we used the Rijksmuseum Image Performance Tool (RIPT) for this check, which allows the measured values of the colour chart to be easily compared with those from the on-site capture. If there are any deviations, we use international standards to then check if they still fall within the correct margins. Meemoo carries out this control after the capture, but it is also done by the photographer immediately when they record the various measurement values. Meemoo actually used this method for the last category as well: gigapixel recordings.

As the icing on the cake, we captured a limited set of masterpieces using gigapixel photography. This is extra special because this technology enables you to zoom in to even the very smallest paint splatter! Professional photographer Rik Klein Gotink took his place behind the lens and captured the finest details of 25 masterpieces in the highest quality.

With the List of Flemish Masterpieces in hand, meemoo, in consultation with the Flemish Masterpieces Board, mainly selected very large works that are less accessible for spotting small details, as well as works with very fine details, for gigapixel photography.

Gigapixel photography is similar to 2D photography, but with some key differences. Instead of taking one photo of a work, dozens of captures are made per masterpiece. In this project, we took as many as 50 different captures per object. And that’s quite time-consuming! A professional photographer can easily spend 4 to 5 hours on just one artwork that is 4 metres high and 2.5 metres wide, using a high-quality camera on a special tripod with a remote control – absolutely essential when the camera is hanging 5 metres high in the air!

Once the photos have all been taken successfully, all the images are assembled into one large file, sometimes tens of gigabytes (GB) in size, which allows you to zoom in to your heart’s content. This is a large patchwork of high-quality images, put together using specialist software (Photoshop or PTGui), using a technique called ‘stitching’.

The quality control for gigapixel captures is done in the same way as for the 2D captures.

The result of a gigapixel capture is a very large file that can only be opened with a powerful computer and appropriate software. With this software, you can take out the smallest details in the highest resolution. Useful for publications, but mainly reserved for professionals! That’s why meemoo provides a much smaller derivative, so that everyone can enjoy the work.

This project was made possible with support from the European Regional Development Fund and is part of the Flemish Government’s Resilience Recovery Plan.