Digitising glass plates, transparent photographic carriers from the 18th and 19th centuries, is no easy task. These unique witnesses to history are fragile and come in all shapes and sizes, which affects the digitisation approach. The Coordinated Initiative for Flemish Heritage Digitisation (GIVE) project, led by meemoo, is digitising a massive amount of images. Below is a detailed account of the process from start to finish.

Preserving and making the content on glass plates accessible involves a meticulous process. The first step is to register and package the materials together with the 33 participating collection managers. Each glass plate is examined and described in detail, with around 50 registrars rolling up their sleeves in the belief that ‘many hands make light work’. In a remarkable 270 days, they registered and packaged 180,000 glass plates, averaging over 600 per day.

As indicated above, registration is a time-consuming and labour-intensive task, but it pays off. Both technical and content-related data are meticulously recorded. Technical data, such as the dimensions and colour of the photo, is crucial for creating high-resolution digital copies. An interesting fact: approximately 97% of all glass plates are black and white! Content-related metadata, such as the title and date, play a vital role in the content's searchability.

We also documented any damage. Glass plates are not immune to the passage of time: the glass can break or corrode, and the photographic emulsion layer can detach, discolour or even develop mould. Despite good storage conditions, these imperfections are caused by the self-destructive nature of the photo carrier itself. Let’s dive into the numbers. Registrars noticed signs of damage in around 90% of the carriers in the GIVE project. This can range from a simple piece of tape on the glass plate (16%) to scratches (9%), cracks (5%) or even fractures (0.4%).

Registering these damage characteristics is an essential step to facilitating a smooth digitisation process and gaining a good overview of the condition of the materials across the various organisations. It is also crucial for subsequent quality control processes because it helps determine whether a discoloured edge was already present on the plate or if it’s a flaw in the digital image. It’s worth noting that damage cannot always be spotted in the digital image.

The next step is to repackage the fragile carriers. During registration, each glass plate is given a new acid-free paper covering. They are then placed together in a sturdy acid-free paper box, which in turn is placed in a shockproof and climate-controlled container. Safe for transportation: check!

GMS, a specialist digitisation company from Sliedrecht in the Netherlands, handled the digitisation side of the GIVE glass plates project. The biggest challenge they faced was to provide equally high-quality digital images for diverse source materials.

To scan or to photograph, that is the question. The latter option was chosen in the GIVE glass plates project for several reasons. Scanners heat up quickly, which can be dangerous for a glass plate’s photographic emulsion layer. This layer is a thin gelatine coating containing light-sensitive silver salts. Conversely, a plate can also damage the scanner. And glass plates are often too thick to fit between the scanner’s surfaces anyway. It is therefore crucial to always remain highly attentive!

There are also other reasons to opt for photographic capture, e.g. photos yield higher-quality and more accurate images, and the process is simply faster.

But there are still some important points for attention. The transparent nature of the material means that using a light source from below is an additional factor to consider. If there is a label with text on the top of the glass plate, additional light from above is needed to make this detail readable. This so-called reflective light was also used for all glass positives.

All of this took place in a specialist studio at GMS, and a mobile digitisation studio was brought to the partners themselves for about a third of the glass plates. This was the case for Ghent University and FOMU (Photography Museum Antwerp). Running two digitisation lines in parallel speeded up the digitisation process, and avoided the external transportation risk for a third of the glass plates. The pace of this digitisation was also incredibly fast: 6,100 glass plates were provided with a digital counterpart every week on average. Some weeks even saw more than 10,000 glass plates pass under the camera!

The aim of the GIVE project is to create high-quality digital copies, preserve them for the future, and make them reusable for various applications. GMS uses specially equipped studios and a unique method to achieve this. What does the process look like?

The camera is correctly set up;

The scanning surface is cleaned;

The required technical specifications are checked and adjusted if necessary through the use of targets;

The glass plate is unpacked, inspected and dry cleaned;

The glass plate is placed on the scanner surface with the emulsion side facing upwards;

Time for capturing!

The glass plate is then packaged up again and safely returned to its box.

Every day, meemoo and GMS configure and extensively test all the technical requirements – the correct aperture, resolution per dimension, white balance and tonal scale. This is done using targets – cards and scales that check the camera settings. Metadata about the digitisation process is also added, and the physical object is linked to the digital capture. Depending on the physical size of the glass plate, the resolution is either 600, 1200 or 1800 PPI.

This crucial measuring instrument for colour, lighting, white balance, resolution and more consists of standardised colour cards and tonal scales. We ensure that everything is done correctly by digitally capturing these targets and comparing any deviations with the reference values. They are the ideal allies for consistency throughout a digitisation project.

Did you know that GMS sorts the glass plates for digitisation by size and type? They do this because each resolution requires different camera settings, and therefore new tests. Sorting is simply a pure time-saving matter.

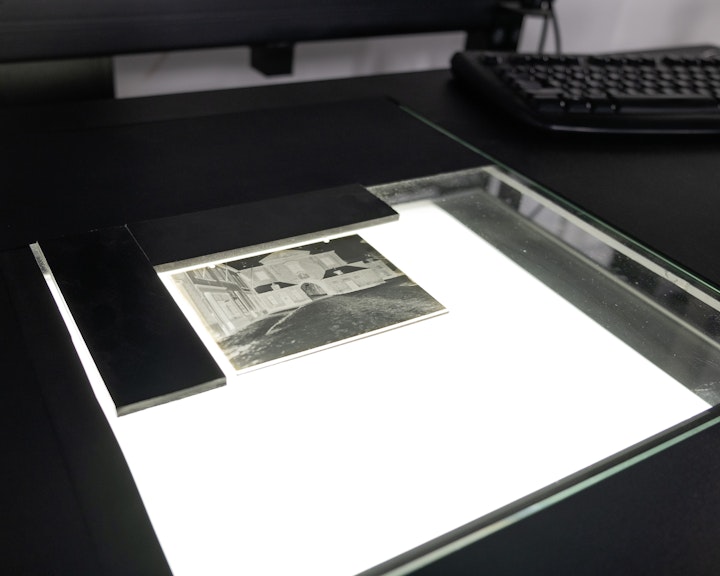

After unpacking, each glass plate is inspected and carefully dusted with a soft brush before being placed on a transparent surface with a light source below. If it is a glass positive or if there is a label on the carrier, a light source is also positioned from above. Next, a camera is put in place perpendicular to the plate and carefully configured based on the format and other technical characteristics. With a simple press of a button, the digitisation is complete!

It looks something like this:

At the start of this project, there were no fixed standards for digitising transparent materials. These standards define, for example, the quality of the digital images, how to set up the process, or how to measure it. Technical agreements tailored to each glass plate variant were established for this project through intensive collaboration between meemoo, GMS and experts such as Bruno Vandermeulen and KU Leuven. Depending on the specific transparent material and the chosen digitisation partner, this new set of agreements can now also be used for other projects.

After digitisation, the digital image is adjusted further – a process called post-production. This additional step allows the images to be widely accessed, e.g. cropping unnecessary space around the digital copies to the edge of the glass plate. This ensures the glass plate remains visible as an object rather than a pure photograph. If necessary, photos are also straightened, always in multiples of 90°.

The most significant amount of work takes place with the glass negatives. These images are converted into positive images, horizontally mirrored, and their contrast is adjusted. They are mirrored because each glass plate is captured with the emulsion side facing upwards for protection, which means that glass negatives are actually captured in reverse. This is therefore corrected during post-processing. Glass negatives are also often under- or over-exposed, so the contrast is enhanced in their digital images to achieve a more neutral exposure across all of them.

Then the digital images are ready for quality control. In addition to daily target checks using Open Dice, meemoo verifies the supplied files for completeness and conducts a visual inspection using XnViewMP image viewer software. Are the images sharp? Has too much been cropped? Are the images nicely mirrored? The files are checked – in TIFF format – for content and structure using DPF Manager. The correct TIFF profile is crucial for their long-term preservation. Baseline TIFF 6.0 was chosen in the GIVE glass plate project.

The glass plate as a complex object: TIFF and DNG

Since one glass plate contains one image, it makes sense to archive the digitised glass plate as a single object. This creates one image file accompanied by a metadata file. However, a multiple object – multiple image and metadata files created for one object – offers more advantages in terms of archiving and accessibility.

We therefore chose RAW files in the DNG file format for archiving in the GIVE glass plate project. This format is future-proof and flexible. It also has broader support and Adobe, the developer of DNG, has released the specification for free. Additionally, RAW files can be further edited without losing the original data in the file. These edits are saved in a reproduction file in TIFF format. This is particularly important for digitised negatives, as various edits often need to be made before they produce a usable positive image, which ensures the DNG file therefore becomes a faithful copy of the glass plate, and the TIFF file becomes a widely accessible image.

Once everything is in order, the digital glass plates are ready to flow into the meemoo archive system. The glass plate managers can then also perform a visual inspection and the glass plates can be gradually made accessible. This can be done either by the project partners themselves or like the selection on this website. Eventually, everyone can enjoy this magical visual content.

This project was made possible with support from the European Regional Development Fund and is part of the Flemish Government’s Resilience Recovery Plan.